Perception as epistemic: 'We PERCEIVE only what we have motivationally selected as entities'

Dr Edmond Wright

If a sensory field exists as a pure natural sign open to all kinds of interpretation as evidence (see 'Sensing as non-epistemic'), what is it that does the interpreting? Borrowing from the old Gestalt psychologists, I have proposed a gestalt module that picks out wholes from the turmoil, it being the process of noticing or attending to, but the important difference from Koffka and Köhler (Koffka, 1935; Köhler, 1940), the originators of the term 'gestalt' in the psychology of perception ( is that the emphasis is upon the gestalt projection as motivated. Gestalt-attention of this kind is usually enforced in the first instance by pain or pleasure, and the resulting projections are placed in memory tabbed with fear or desire, such that if such a pattern recurs in the sensory field, fear or desire are triggered. In advanced animals the ability to play with the gestalt module has been evolved, because experimenting in curiosity has proved adaptive, as the exploratory behaviour in the Rat, the Raven, the Apes and Homo sapiens bears out.

This is perhaps, too, what Putnam, in spite of himself, is indirectly insisting on when he says, 'Cut the pie anyway you like. Meanings just ain't in the head' (1975, 227), for he too does not consider that the choices are from a continuum. He considers the pie cut at given joints - but pies don't have joints, and the continuum doesn't have given discrete boundaries - for the sensory field should itself be seen as part of nature, not yet organized into useful epistemic units.

What, after all, is the essential character of any evidence? Take the grain of the wood of the huge cross-section of a Sequoia tree shown in a scene of Alfred Hitchcock's film Vertigo. In that scene we see that someone has identified and labelled certain of the circular bands in the wood as laid down in particular years. One might even with closer enquiry and comparison be able to find out from those which years had had, say, heavy rainfall and which exceptionally cold winters. But no one would say, except metaphorically, that there was 'information' in those bands. Similarly, one cannot say that there is 'information' about objects and properties of the world around you in the light-rays that come to your eyes and the sound-waves that come to your ears. This is what is meant by saying that the sensory fields and what they respond to are non-epistemic. They merely provide structurally isomorphic evidence that has to be inspected and learned from under the regime of our desires and fears. Any detective story can illustrate how evidence is virtually infinite in what it can yield to inspection. You may have seen a depression in the ground, if, indeed, it came to your notice at all: Inspector Morse, however, sees a footprint, and then, in closer inspection, the footprint of a woman, then of one with a limp, and so on and so on. There is no strict limit on what can be derived from evidence, since evidence after all is just part of nature. This is what Hermann von Helmholtz maintained: 'Helmholtz sets out for us the proposition that our sensations are for our consciousness signs, the meaning of which is to be learnt by our understanding' (Sully, 1878, 182). What needs correcting in this assertion is that it is not 'meaning' that is given, but bare evidence. We have to learn what to take as a 'sign', for the Real. Always ready to surprise us, enforces a constant adjustment of our co-operative guesses.

Jean Piaget has detailed how each of us under this regime of motivation comes to refine incessantly our selections from the evidence (Piaget, 1970). Pain stamps into memory a first rough approximation, a memory attended by fear; pleasure an approximation attended by desire. Such initial memories are not immediately sufficiently adaptive: consequent experiences produce a greater and greater degree of approximation to the current external cause, a kind of feedback which remains ever open to adjustment. Roy Wood Sellars called it a 'from-and-to' adjustment (Sellars, 1970, 125). This can be readily seen to be necessary since there is no guarantee that the cause in the Real will remain in its initial state. Piaget called this endless process of adjustment that of 'assimilation' and 'accommodation', in that there is an 'accommodation to reality of the schematism of assimilation' (Piaget, 1955, xii), the latter being the motivational pattern that the organism is born with in the service of its life-maintaining and species-reproductive demands. Piaget recognised that all objectification was an endless process of approximation out of an 'undifferentiated' field, but could not make the last step of allowing that the final singularity of 'the object' was in fact an illusion; he could only say

The existence of the object (i.e. the object as limit) constitutes the only possible explanation of the directed approximations, even if one is never certain of having attained the end and even if the knowledge acquired in the course of this history prevents us believing in all ultimate characteristics (Piaget 1969, 116)

He did not see the part played by the needful common trust in maintaining a fictive final end of the procession of 'accommodations'. Since there is no way in which our sensing or what we have individually learned can be perfectly matched, our 'accommodations' can never absolutely converge. Our trust must always be aware of that inescapable risk: that is what real trust is, allowing the other person their own view of 'things'.

These accommodations are our epistemic selections from the undifferentiated fields of sensory experience. Instead of being faced with an unorganised chaos, we immediately re-cognise regions and features, which we characterize as 'entities' (things, animals, persons, etc.) and 'properties' (colours, tones, velocities, sizes, etc.). This familiar world is what is perceived and known, but it still contains the sensory as its evidence, and like all evidence from it can emerge the unexpected. As Freud would say, it can turn 'uncanny' on us, defeating our intentions where we least expect (Freud, 1985/1919). The longer-lasting and more habitual our perceptions, the more we are tempted into turning their objective reliability into logical certainty, to the point where the fact that they were all generated by the pleasure/desire-pain/fear system is forgotten. Their array becomes a comfortable 'reality' full of reassurance, hiding its guess-like character under its repeated successes, whereas the truth is that that familiar array is the record throughout history of the efforts of our species in innumerable acts of fear and desire to cope with the threatening and rewarding contingencies of the Real. Here one might credit Arthur Schopenhauer with being the first to point to this in his insistence that the world was a creation of Will out of bare sensation (the non-epistemic), the wills of all our ancestors as well as that of our own and those with whom we have spoken. No wonder we use the word 'familiar' of those heimlich tables and chairs, cats and trees, that make up our cosy 'reality', for it is all the experience and all the talk of the human family that has enabled us to make those cognitions. Human history is working at this very moment in all your identifications, of this page and this print, as well as that of your self. Speech, within this theory (see the Language section) becomes our means of updating each other on the best selections 'to will' from the Real. No wonder St. John's gospel begins with saying that 'In the beginning was the Word and the Word was God' for 'we' could not even identify 'ourselves' or the 'reality' about us without all that has been done before us by our human forebears.

This theory thus shows a way to interpret Kant's well-known dictum, 'Thoughts without content are empty: intuitions without concepts are blind' (Critique of Pure Reason, A51), 'Intuition' was Kant's word for pure sensing, so his epigram means 'thinking not related and informed by sensation is useless for it would have no relevance to the world: but, equally, sensation alone cannot provide knowledge, for it is bare of understanding, non-epistemic.' One can go further: if sensing as such is metaphorically 'blind', contains no knowledge, it also contains no desire or fear, no motivation whatsoever. It is the gestalts that carry the motivation into the natural sign, a motivation that is always alert to project new significance upon so-far unselected portions. Even the embedding in memory is iconic, that is, more evidence goes into the memory than is captured in the conscious concept. This allows for later examination of them in the mind at leisure and possible discovery from them of new significances, a real evolutionary advantage. Even in memory the non-epistemic remains within the epistemic.

An amusing direct proof of this is as follows. It only works for those who are what the psychologists call 'audiles', that is, those who can mentally image sounds in their head at will, in this case, a voice. If you are an audile, then, let your internal voice say 'Bell-I-Mud-Dum' over and over in succession without stopping (i.e. 'Bell-I-Mud-Dum, Bell-I-Mud-Dum...' etc.; see Skinner, 1957, 282), but stop reading now in order to avoid seeing what is in the next paragraph.

How long was it before you realised you were saying 'I'm a dumb-bell'? If you succeeded in making the change - some people do, others do not - the non-epistemic mentally-imaged sensory sound was turned from one epistemic interpretation into another. Of further important significance in this little example is the fact that the boundaries of the objects within it changed: instead of the two words 'I-Mud', we have 'I'm a d-', strictly three words and part of another. The gestalt boundaries have changed. Notice, too, that the joke worked because I updated you from a mistake, a 'mis-take', revealing you to be stupid, a 'dumb-bell', furthermore one whom I have induced into declaring him- or herself to be so! The will was clearly involved in that little episode of gestalt-switching (see the Joke and Story section). This amusing but cogent demonstration completely refutes the claims of those (for example, Zenon Pylyshyn, 2002) that all mental imagery is stored in a propositional form.

This evolutionary advantage of this ability is based on the pain-pleasure/fear-desire system being the essential feedback module that governs the selection of action-guiding percept-gestalts from the raw fields, which renders these gestalts continually adjustable. New 'entities' are projectible, their spatio-temporal and qualitative boundaries remaining flexible, precisely to allow for the needful disambiguation where the environment fails to conform with the original fixation. This is just what Gerald Edelman argues for in neurophysiology (Edelman, 1989), the evolution of percepts under a regime of value. A serial-digital robot is incapable of such transformations of concept since its world has to be characterized, not in terms of open evidence, but as one might say, in terms, that is with the external environment already considered to be presented in given chunks of information - 'edges', 'corners', 'discs', 'cylinders', etc. Because of this, however long and detailed the list of fixed criteria from which it derives its learning abilities, it is always finally open to being trapped in a maladaptive repetition from which it is incapable of escaping. Advanced organisms, fortunately, are not hobbled by such limitations, but are able in their varying degrees to range over the open evidence of the sensory in adaptive flexibility.

At the human level, because of individual differences between persons, the possibilities are opened up of (a) within an apparently 'common' gestalt bringing to notice a feature that for others had remained non-epistemic but which a particular observer came to realize was significant for successful action; and (b) projecting a gestalt in situations unexpected by others. The agreements that are made about these projections will therefore inevitably have concealed elements of mismatch, both at the sensory level (because of differences of registration), and at the epistemic one (because of differences of intentional perspective). Since these agreements are about what are termed such 'entities' as selves, other persons, and things, the question of difference is a critical one. These concealed disagreements are themselves a proof of the non-epistemic in sensing, for it shows plainly that the public word does not capture all the private sensation. As I have put it before: 'What is implicit for each cannot all be explicit for both' (Wright, 1978).

Since natural signs do not come with their information stamped on them, it is a matter of learned interpretation as to whether the 'things' that we choose to outline from the field have the chosen boundaries and characteristics that will serve us in action. Pragmatic dialogue about these differences is inevitable, leading to new decisions about what is to constitute a particular thing. John McDowell considers the fact that interpretations can change in this way, and he professes himself puzzled by it, thus: 'This strikes me as making it impossible to claim that the argument traffics in any genuine idea of being in touch with something in particular' (McDowell, 1994, 17). It is true that in this theory we do not have access to 'things in particular', since 'they' are only the provisional gestalts that we each individually project upon the natural-sign field in the work of co-ordination with others, but the field itself and the continuum with which it is in isomorphic relation are both existent. There are certainly viscous conglomerations in the continuum that change less fast than others, but they do not come already gelled. To use the current cliché, we have to act together as if that there are precise joints in the real in order to carve it. As Richard Gregory and I have both argued in the same volume recently (Gregory, 1993, 259; Wright, 1993, 194), 'things' are, strictly speaking, non-existent, being but the ideal coinciding of all our numerically separate object-hypotheses. 'Things' are part of a useful folk-psychological, co-operative method by which we try to hold our tentative convergences upon the real continuum.

The Causal Theory of Perception is therefore false because it is an Object -Causal theory. A discussion in The Philosophical Quarterly during the last decade on the Causal Theory of Perception was vitiated on both sides of the argument by the turning of the needful assumption that there are objects into a blind conviction that there are such. Note for example, how William Child (1992) quotes Donald Davidson and Peter Strawson approvingly, but the quotations show both treating assumption as something more than assumption: 'we must, in the plainest and methodologically most basic cases, take the objects of a belief to be the causes of that belief (Davidson, 1986, 317-318), 'For we think of perception as a way, indeed, the basic way, of informing ourselves about the world of independently existing things' (Strawson, 1979, 103) (my italics in both). The reply to these assertions should by now be obvious: it is to say, 'Exactly! We have to take the objects of a belief to be the causes of that belief, although "they" are not' and 'Yes, we must think of perception as if we are informing ourselves about a world of independently existing things, although we know there are in fact no such perfectly singular things.' Davidson and Strawson are both turning a postulate that they themselves express -for their own words give them away - into a given fact. In this they are doing the same thing in word and virtually in thought that the German Idealist philosopher F. W. J. von Schelling did in expressing his belief that ultimately the Absolute in the Object is identical with the Absolute in the Subject. Note how in the following he cannot avoid using the words 'assumption', 'take ... to be' and 'presupposition', though what he means to imply is that absolute identity between appearance and reality is a fact:

The assumption that things are just what we take them to be so that we are acquainted with them as they are in themselves underlies the possibility of experience, for what would experience be without this presupposition of absolute identity between appearance and reality? (my italics)

In the same debate, Gerald Vision (1992, 346), in considering situations where a reconceptualization is involved, takes Shakespeare's Antipholus of Ephesus who first sees Dromio of Syracuse as Dromio of Ephesus and then later learns the truth, but this also takes for granted that the reconceptualization was of an entity the singularity of which was undisputed to the exactly the same entity, which is a failure to generalize: the correct generalization must include situations in which allows the very boundaries of 'the entity' to be re-drawn, as we saw in the 'Bell-I-Mud-Dum' example. When the bush mentioned by Shakespeare's Duke Theseus turned into a bear because someone was 'imagining some fear', it was not necessarily all of the bush that necessarily changed into the whole of the bear, for there might have been a projecting branch that we did not notice when we saw the Bear gestalt, but which we, consciously unaware of the change, see as part of the bush on a second inspection. As the sixth-century Indian philosopher Dignaga said, 'Even "this" may be a case of mistaken identity' (Matilal, 1986, 332).

Existence and objectivity thus logically come apart, even though each observer has picked out for him- or herself a real portion of the field and called it 'the' object. What is certainly not the case is that precisely the same portion of the external world is picked out by everybody: the ideal singular object common to all of us does not exist. It is only through the participants in this language-game acting as if there is 'one' object that a fuzzy overlapping of perspectives is achieved on some fairly viscous region of the flux.

To borrow Robert Van Gulick's phrasing, our individual, numerically separate and therefore partially opaque 'semantic selections' are treated as if they are perfectly mutually transparent (Van Gulick, 1993). According to Kant, 'To one man, for instance, a certain word suggests one thing, to another some other thing; the unity of consciousness in that which is empirical is not, as regards what is given, necessarily and universally valid, (CPR , B140). The possibility that Kant did not realize, although it is implicit in his own words, is the fact that the most common situation is one in which the two 'things' mentioned in this statement are most commonly taken to be one 'thing' by the persons concerned. Putting the present proposal in Kant's terms, the 'transcendental unity of apperception, that unity through which all the manifold is given in an intuition, is united in the concept of an object' (ibid.) is to be distinguished from any empirical unity. The reason is that Kant's two agents are projecting that 'transcendental unity' as a method of co-ordination while still taking their numerically separate selections from the 'noumenon' as their own view of the 'object'. Thus, in the social production of knowledge, we can talk in hypothetical terms of ontologically real singular objects, but these have no causal part to play, whereas the material continuum does. Another way of describing this useful game of co-ordination is to say that we are following the practical rule of treating all our individual 'seeing-as's' as 'seeing-that's'. This is what sharing perceptions is.

The very viability of our interpretations, the fact that they can be usefully, intersubjectively updated is what proves the existence of the real field-as-a-whole and its real cause. This theory cannot therefore be accused of falling into the idealist error of hiding the Real behind appearances, for it contends that appearances, the sensory, are but a part of the Real. It can be said that all our informative communications are cases of such intersubjective feedback. It should also be obvious that, from this point of view, any objectivist externalist argument has begun with a false premiss (Burge, 1986): it takes for granted the existence of external objects without realizing that 'taking them for granted' is but the method by which a fuzzy mutual co-ordination is achieved.

Our very method of obtaining a satisfactory even if only viable mutual hold is thus to assure each other that we are achieving one, but this is only the necessary method of maintaining a sufficient overlap of individual plural identifications, not a guarantee of a real singular logical identity, only of a hypothetical one. The important thing is that we need this hypothetical overlap-taken-to-be-a-perfect-superimposition in order to get our separate views aligned ready for any needful correction from each other. From the present point of view, this is the 'tradition' of which Gadamer speaks that is to be postulated within the 'fusion of horizons' (Gadamer, 1975). A key distinction (enlarged upon in the Faith section) is that this structure of practical and communicative relation is something that has evolved in the human species, and therefore is not in itself normative. It has the pattern of a loose trust but is not a genuine trust unless, consciously or unconsciously, the partners in action and dialogue are prepared to see that the trust must compass the recognition that one's partner cannot understand in the same way as oneself.

When David Wiggins, who correctly asserts that 'there are no lines in nature' (1986, 170), assures us that all our vaguenesses with respect to 'an' object 'match exactly' (175), he is only exhorting us into this needful fictive ploy of a perfect coinciding, for in the real world something in my 'vagueness' may turn out to be significantly different from what is to be found in yours. To explain this another way, it is possible of two persons, A and B, that each one is making assumptions that are not salient to both, so that neither know exactly what it is that is sensorily included in his or her percept that is not included in the other's. F. C. S. Schiller called this needful ploy or play in which we act as if our vaguenesses matched exactly a 'feigning of the non-existence of differences' (Schiller, 1929, 164), a feigning of logical identity across our differing identifications that does service for a real one. Putnam has doubted whether our identification of common objects, as in 'There are a lot of cats in the neighbourhood', could be dismissed as mere folk-psychology (Putnam, 1988, 2), but here we see a way in which it can. Our talk of objects is folk-psychology, but it is indispensable to our practice in the world.

All applied rationality is folk-psychological, based on a common faith in each other. The pure rationality of logic and mathematics, on the other hand, requires no faith, since it never has to be tested out against people's interpretations of the real - it involves no outcomes that could affect our desires and our fears, for none of its symbols refer to the Real. There is no reference in pure logic and mathematics; in fact, if it does slip unawares into referring, the result is a paradox, for we are virtually saying to ourselves 'This language game we are engaging of not referring to the world does refer to the world'. Zeno's paradoxes (such as the 'Achilles and the Tortoise'), for example, all depend on the impossible reference to something so small that no mutual agreement about that portion as a part of the Real could ever be reached (this point was made in 1836 by Alexander Bryan Johnson, 1968/1836, 100). The paradox in Gödel's Proof of the Inconsistency of Mathematics arises because it contains an attempt to refer, namely, in making numbers refer to other numbers. Treating numbers as never referring makes them of course the most fictive of all uses of language: ordinary words may only refer by virtue of our mutual idealization, but at least they retain a current tenuous hold on the Real. In pure mathematics the logos becomes pure mythos.

Even though we in all trust might take for granted that nothing the other understands but has not made mutually salient could be to one's own disadvantage, our social partner may in all innocence be understanding something that be of great danger to us. After all, the term 'take for granted' includes those slippery words 'take for' and what do they mean? Do we not use them thus, say, of a figure in the fog, 'I took him for his brother', that is, 'to take for' is to accept an illusion of one thing for another thing, and what in this case is the illusion we are taking for real? - Why, our granting something - and what is 'to grant'? - It is to say that there is nothing in the case that will be to our disadvantage, discomfort, or actual hurt, for our body is involved. Maurice Merleau-Ponty said that 'this presumption on reason's part' (his italics), this postulation of 'a totally explicit knowledge', was 'the fundamental philosophic problem' (1970, 63). (The philosophers Roy Wood Sellars and Clarence Irving Lewis, the sociologist Alfred Schutz and the psycholinguist Rommetveit have independently pointed the way to its solution; see the Faith section).

Another story, this time to illustrate the process of perceptual reference as played by two agents. Albeit a story, it can be taken as a logical generalization for the nature of all reference, which has been such a conundrum for philosophers, a real philosophical riddle. It also illustrates how trust can be innocently undermined.

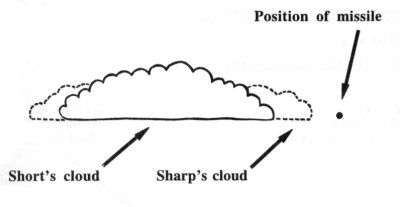

Two military observers are on the watch one evening. Their task is to keep an eye open for enemy missiles; they have an anti-missile launcher of an antique type, which is guided by them directly but which is rather slow to respond to a new directional setting once it has been aimed, so they have to be very speedy with their initial reactions. One is called Short (he happens to be short-sighted); his companion is Sharp (he happens to be sharp-sighted). The day has been peaceful and, as evening approaches and the sun is setting, (time1) Short says to Sharp, "What a beautiful cloud!" This is what lies before them in the west, a long band of water-vapour, a stratus-cloud, which has faint fringes on each side of it.

Those faint fringes are invisible to Short but visible to Sharp, though neither of them are aware of this difference in their sensory registration. Nevertheless, Sharp readily agrees: "Yes. What a beautiful cloud!" The fact that Short was particularly impressed with the tint in the central part of the cloud and Sharp by the delicacy of the fringes was irrelevant in this case. They had both achieved a common reference by their own lights. There was 'one' object before them, and Short had managed to make salient something about it to Sharp which he had not noticed before and which brought him pleasure. They had achieved a common understanding about it; their communicative trust has been sustained in its experiment with the Real. 'To all intents and purposes', as they might have said, a communication had gone through and about a commonly recognisable portion of nature. We, of course, must add, 'to all mutually salient intents and purposes'. The very phrase itself in common use carries with it a scintilla of doubt, for 'to all intents and purposes' is often used in situations in which we think some substitution is involved (e.g. 'To all intents and purposes, he was the bank manager.').

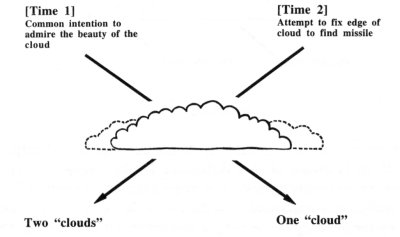

However, to get back to our story: At time2, Sharp, who is not at that moment responsible for directing the missile-launcher, notices an approaching enemy missile and he immediately alerts Short. "Where is it?" cries Short. "At the edge of the cloud on the right!" shouts Sharp (at the place shown by the dot in the diagram). Short now aims at 'the edge of the cloud on the right'. One need not describe the consequences at any length, but merely add - End of Short and Sharp.

What the story illustrates about reference is that the selections we privately make from the continuum of nature and that we endeavour continually to keep in public co-ordination are dependent upon the percepts we have individually made from our own sensory fields, and that these selections are driven by motivation as the essential initial feedback, which can be later updated by communication from another. However, these perceptual selections can only ever be viable, that is, apparently confirmed by the circumstances that have existed up to that point in time. Our common understandings can only be sustained by the tests that one has so far applied, and there is no guarantee that all criteria relevant to a new situation will already have been made salient to both parties. This is the point that has been made repeatedly and with great clarity by the psychologist Ernst von Glasersfeld (e.g. 1984) from whom we borrow the useful word 'viable'.

One can now enlarge the diagram to show, as before with the riddle, above the ambiguous 'cloud', the rival contexts of interpretation, and, below it, the rival meanings produced by them.

In answer to this Merleau-Ponty might have quoted a passage from Phenomenology of Perception (1970, 54) in which he virtually says all that is argued for here:

The tacit assumption of perception is that at every instant experience can be co-ordinated with that of the previous instant and that of the following, and my perspective with that of other consciousnesses - that all contradictions can be removed, that monadic and intersubjective experience is one unbroken text - that what is indeterminate for me could become determinate for a more complete knowledge, which is, as it were, realized in advance of the thing, or rather which is the thing itself.

But this is the Story of Short and Sharp: they did all that Merleau-Ponty could have expected of them, but what caught them out? A difference in sensory registration which had not been obvious to either of them, a part of the non-epistemic. The reciprocity cannot be 'consummate', only as the mutually hypothesized consummate co-ordination that is never achieved. Merleau-Ponty did say 'as it were', and interestingly used the word 'text' of the idealization.

Of poor Short and Sharp, although their gestalts from their point of view had embraced all they could see in their visual field, nevertheless there was a sensory feature that was not captured in the public word. But Merleau-Ponty's claim for a dialectical structure is correct. He is right to insist that there is a 'certain fundamental divergence, a certain constitutive dissonance' between agents that allows for a creative dialectic to occur (1968, 234). What can now be understood is that it will not work unless he concedes that there is a sensory level which is not capturable in the terms that we use in our public language. Émile Brehier criticized Merleau-Ponty for not giving due place to the sensory immediate (Brehier, 1964), yet Merleau-Ponty repeatedly stressed the inexhaustibility of the sensory. What he should have gone on to conclude, and inconsistently did not, is that it is differently inexhaustible for each body. If it is, it is therefore not capturable in the common object-term two agents are using for what they take to be the same portion of the continuum that is of motivational concern to both. Merleau-Ponty should have heeded his own term 'play' in his phrase 'intersubjective play' for play is precisely created by the provision of a clue to a rival context that transforms the meaning of a portion of the continuum (take the chimpanzee' s special grin that indicates that the attack on his fellow is not a real one; see Bateson, 1978, 152).

A precisely similar diagram to those above can be used to analyse play. Indeed. the highest moments in a game are those in which player A has just produced what every one thinks is a winning stroke, but player B, being a master, perceives the very weakness created by that winning stroke (only faintly indicated and thus missed by those over-impressed by the wrong clue) and takes advantage of it to everyone's delighted surprise. Consider judo, in which one takes advantage of one's opponent's own momentum in making his apparently irresistible attack. The Game, the Story, the Riddle, the Joke, and the Statement are all exactly alike in this, and it is no 'family resemblance' (see the section on the Joke).

References

Gregory Bateson (1978) Steps to an Ecology of Mind. London: Granada.

Brehier, Émile (1964) 'Discussion' in Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Primacy of Perception (see below), pp. 27-40.

Burge, Tyler (1986) 'Individualism and psychology', The Philosophical Review, 95, 3-46

Child, William (1992) 'Vision and Experience: The Causal theory and the Disjunctive Perception', Philosophical Quarterly, 42, No. 168, 297-316

Collins, A. W. (1967) The epistemological status of the concept of perception. Philosophical Review 76: 436-59.

Crumley II, Jack S. (1991) 'Appearances can be deceiving'. Philosophical Studies, 64, 233-51.

Davidson, Donald (1986) 'A Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge', in Ernest LePore (ed.), Truth and Interpretation: Perspectives on the Philosophy of Donald Davidson. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, pp. 307-19.

Dennett, Daniel C. (1991) Consciousness Explained. London: Penguin Press.

Evans, Gareth (1982) The Varieties of Reference. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Feigl, Herbert (1958) 'The "Mental" and the "Physical"', in Herbert Feigl, Michael Scriven and Grover Maxwell (eds.), Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Vol. II: Concepts, Theories and the Mind-Body Problem. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, pp. 370-497.

Foster, John (2000) The Nature of Perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Freud, Sigmund (1985/1919) 'The uncanny' in Art and Literature, Vol. 14, The Pelican Freud Library, ed. Albert Dickson. Harmondsworth: Pelican Books, pp. 335-76.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg (1975/1960) Truth and Method. Trans. Garrett Barden and John Cumming. London: Sheed and Ward.

Gibson, James J. (1968) The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems. London: Allen and Unwin.

Ernst von Glasersfeld (1984) 'An introduction to Radical Constructivism', in The Invented Reality, edited by Paul Watzlawick. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., pp. 17-40.

Gregory Richard L. (1983) 'Perception: Psychological issues', in Rom Harré and Roger Lamb, The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford: Blackwell. Pp. 450-2.

Grice, H. P. (1967) 'Meaning', in P. F. Strawson (ed.), Philosophical Logic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 39-48.

Harman, Gilbert (1990) 'The intrinsic quality of experience', in J. Tomberlin (ed.), Philosophical Perspectives, 4: Action Theory and the Philosophy of Mind. Atascadero, California: Ridgeview Pub. Co., pp 31-52.

Helmholtz, Hermann von (1901) Popular Lectures on Scientific Subjects: First Series. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Hermann von Helmholtz (1968) Helmholtz on Perception: Its Physiology and Development. Eds. Richard M. Warren and Roslyn P. Warren. New York; John Wiley.

Hermelin, Beate (1976) 'Coding and the sense modalities', in L. Wing (ed.), Early Childhood Autism; Clinical, Educational and Social Aspects. Oxford: Pergamon Press, pp. 135-68.

Horubichi, Seiji and Inoue, Yuki (1994) Stereogram. London: Boxtree.

Huemer, Michael (2001) Skepticism and The Veil of Perception. Lanham, Boulder, New York and London: Owman and Littlefield.

Jackson, Frank (1977) Perception. A Representative Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, Alexander Bryan (1968/1836) A Treatise on Language. Ed. David Rynin. New York: Dover Publications.

Kant, E. (1787/1964) The Critique of Pure Reason. London: Macmillan.

Kirk, Robert (1994) Raw Feeling: A Philosophical Account of the Essence of Consciousness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Köhler, Wolfgang (1940) Dynamics in Psychology. New York: Liveright.

Koffka, Kurt (1935) Principles of Gestalt Psychology. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Kosslyn, S. M. (1994) Image and Brain: The resolution of the Imagery Debate. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Marr, David (1982) Vision. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Matilal, Bimal Krishna 1986: Perception: An Essay on Classical Indian Theories of Knowledge. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Maund, J. B. 1993: 'Representation, Pictures and Resemblance', in Edmond Wright (ed.), New Representationalisms: Essays in the Philosophy of Perception. Aldershot: Avebury, pp. 45-69.

McDowell, John (1985) 'Values and Secondary Qualities', in Ted Honderich (ed.), Morality and Objectivity: A Tribute to J. L. Mackie. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, pp. 110-29

McDowell, John (1994) Mind and World. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1964) The Primacy of Perception, and Other Essays in Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics. Trans. William Cobb. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1968) The Visible and the Invisible, translated by Alphonso Lingis, edited by Claude Lefort. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1970) Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Nakajima, N. & Shimojo, S. (1981) Adaptation to the reversal of binocular depth cues: Effects of wearing left-right reversing spectacles on stereoscopic depth-perception. Perception 10: 392-402.

Piaget, Jean (1955) The Child's Construction of Reality. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Piaget, Jean (1969) The Mechanics of Perception. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul

Piaget, Jean (1970) Genetic epistemology. New York: Columbia University Press.

Pitcher, George (1971) A Theory of Perception. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, Hilary (1975) Mind, Language and Reality, Philosophical Papers, Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Price, Henry Habberley (1961/1932) Perception. London: Methuen.

Putnam, Hilary (1988) Representation and Reality. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Pylyshyn, Z. W. (2002) 'Mental imagery: In search of a theory'. Behavioral and Brain Sciences (forthcoming).

Rorty, Richard (1980) Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Ryle, Gilbert (1966) The Concept of Mind. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Sellars, Roy Wood (1916) Critical Realism: A Study of the Nature and Conditions of Knowledge. Chicago, Illinois: Rand McNally & Co.

Sellars, Roy Wood (1930) 'Realism, Naturalism, and Humanism', in George P. Adams and William Pepperell Montague (eds.), Contemporary American Philosophy, Vol. 2. London: George Allen and Unwin, pp. 261-285.

Sellars, Roy Wood (1932): The Philosophy of Physical Realism. New York: Macmillan.

Sellars, Roy Wood (1955): 'My Philosophical Position: A Rejoinder', Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 16/1, 72-97.

Sellars, Roy Wood (1965/1938-39): 'The Aim of Critical Realism', in R. J. Hirst (ed.), Perception and the Physical World.

Sellars, Roy Wood (1970): The Principles, Perspectives and Problems of Philosophy. New York: Pageant Press International

Skinner, B. F. (1957) Verbal behavior. New York: Appleton-Century Crofts.

Strawson, P.F. (1979) 'Perception and its Objects', in G. F. MacDonald (ed.), Perception and Identity: Essays Presented to A. J. Ayer and his Replies to them. London: Macmillan, pp. 41-60.

Van Gulick, Robert (1993) 'Understanding the phenomenal mind: Are we all just armadillos?', in Martin Davies and Glyn W. Humphreys (eds.), Consciousness: Psychological and Philosophical Essays. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, pp. 137- 54.

Vision, Gerald (1992) 'Animadversions on the Causal theory of Perception', Philosophical Quarterly, 43, No. 172, 344-57.

Vision, Gerald (1997) Problems of Vision: Rethinking the Causal Theory of Perception. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Wiggins, David (1986) 'On Singling out an Object Determinately', in Philip Pettit and John McDowell (eds.), Subject, Thought and Context. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 169-80.

Wright, Edmond. L. (1978) 'Sociology and the Irony Model', Sociology 12, 523-43.

Wright, Edmond L. (1983) 'Inspecting images'. Philosophy 58, 51-72.

Wright, Edmond L. (1993) 'The irony of perception', in Edmond Wright (ed.) New Representationalisms: Essays in the Philosophy of Perception. Aldershot: Avebury Press, pp. 176-201.

Wright, Edmond L. (1996) 'What it isn't like'. American Philosophical Quarterly 33:1, 23-42.