The Story of the Story: Invasions from the Real

Dr Edmond Wright

The title of this paper is 'The Story of the Story'. If its argument is valid, I cannot be speaking to you now, trying to change your view of something without telling a story myself, even about the Story. Over the last two decades there has been an increasing number of people in a variety of disciplines telling us that the story, narrative, is an inescapable feature of human communication. Listen to a few representative voices. from psychology - Theodore Sarbin: 'Human beings think, perceive, imagine, and make moral choices according to narrative structures' (Sarbin, 1986,8); from philosophy' - Alasdair MacIntyre: 'In what does the unity of a human life consist? The answer is that its unity is the unity of a narrative embodied in a single life' (MacIntyre, 1981, 203); from literary theory, Donald Polkinghorne: 'Narrative is the primary form through which human beings construct the dimension of their life's meaningfulness and understand it as significant'; from hermeneutics - Paul Ricœur: 'time becomes human to the extent that it is articulated through a narrative mode, and narrative attains its full meaning when it becomes a condition of temporal existence' (Ricœur, 1983, I, 52); from rhetorical studies - Walter Fisher: 'Narration is the foundational conceptual configuration of ideas for our species,... the context for interpreting and assessing all communication ... [and] the shape of knowledge as we first apprehend it'' (Fisher, 1987, 193); from sociology - Richard Harvey Brown: 'Civic communication, ... [and] the logic of science and technology of science and technology can be subsumed under narrative discourse; and ... moral-political life takes a narrative form' (Brown, 1987, 164); from history - Hayden White: 'To raise the question of the nature of narrative is to invite reflection on the very nature of culture and. possibly, even on the nature of humanity itself' (White, 1980, 5); and. finally, from psychoanalysis - Roy Schafer: '"The self is a telling.[ ... ] Other people are constructed in the telling bout them; more exactly, we narrate others just as we narrate selves' (1980, 35).

This is such a remarkable chorus that one wants to look at once for the common feature, the power of which all are attesting to.. The telling of stories is such a spontaneous activity that we even do it in circumstances that would seem to discount it altogether. When the Belgian psychologist Michotte was undertaking his investigation into whether causation was something that could be perceived, he set his subjects to watch the movements of small triangles on a screen. What he discovered serendipitously was that his subjects could not resist anthropomorphizing the triangles and telling stories about them, like this: "It is as if A's approach frightened B and B ran away." Michotte mentioned that the experiment often produced a comical effect and made observers laugh (Michotte, 1963). Where there is a joke, there is a story.

Those of you who were here last year may recall that my topic then was Lacan and the Joke, and it ended with my drawing a parallel between the pattern of a joke and that of a story. My present aim is to extend that analysis to the Story in more detail and to extend the scope of that analysis. The investigation is founded on partly on my own work in the philosophy of perception, but it owes much to the sociologist Alfred Schutz (1962), the psycholinguist Ragnar Rommetveit (1968, 1974, 1978, 1983), and the developmental psychologist Ernst von Glasersfeld (1984, 1989).

Let me begin with one of Sir Ernst Gombrich's diagrams, a development of the Rubin's Vase Illusion, can be taken as an emblem of the argument to be presented here. The diagram that initiates this argument was produced by Gombrich to show the effect of existing memory expectations upon features of the distribution of a visual field. He took the familiar Rubin Vase,

which we can subject to a switch of gestalts between two profiles or a vase. He added clues which strengthened our expectations, first a pair of ears, which encouraged the Profile interpretation:

or a few flowers at the top, which strengthened the Vase interpretation.

His significant move was to include both sets of contextual clues, thus:

He points out that if you mask either set of clues 'the reading becomes assured' (Gombrich, 1973, 239). The interesting aspect of this demonstration is that the rival gestalts play over what is a contestable visual ground which cannot be described in the terms that are used of the gestalts per se. The old gestalt-psychologists would have told us that there is an interchange of what they called 'figure' and 'ground', that is, in the vase gestalt it is the space between the lines that is taken to be filled with an object and the space outside to be taken as the background, in the case of the two profiles it is the spaces on either side that are to be taken as filled with the faces and the space between to be seen as background - which implies that the gestalt-switch is taking place over the black lines and the white spaces. The question arises: how should they be described, because the terms 'black lines' and 'white spaces' is obviously an inadequate description. So it becomes an important question how the basic arrangement is to be described, one which will be seen to be crucial in a consideration of what any story is. The same is shown more markedly in Hamlet's mocking play with gestalts on a cloud:

HAMLET: Do you see yonder cloud that's almost in the shape of a camel?

POLONIUS: By th' mass, and 'tis like a camel indeed.

HAMLET: Methinks it is like a weasel.

POLONIUS: It is backt like a weasel.

HAMLET: Or like a whale?

POLONIUS: Very like a whale.

Now there is no guarantee that the various gestalts produced by this playing with the sight of some random distribution of water-vapour shared the outlines of the same portions of that water-vapour: the 'camel' might have taken up one portion of a chance outline, the 'weasel' another, and the 'whale' yet another. It cannot be assumed that precisely the same portion of this continuum of water-vapour- for a continuum is what it is - was captured by the gestalts that two imaginations in play threw upon it. Nor in the real world can be assumed that both observers have the same sensory registration of it: not only are they looking from different points of view, but it is impossible that their visual registrations are the same, for eyes differ in focus and. further, what is hardly recognized at all differ in the ranges and intensities of their responses to light-waves. Just as my son as a child was able to hear higher frequencies than I could, so there must be people in this room who can see a little further into the ultra-violet or the infra-red than other people. There is much that escapes our everyday agreements about what we see, hear, sense generally, yet is perfectly precise at the level of its registration in our brains. For example, as I hold up my hand and focus on you, if I observe with care without altering my focus, I can see that my hand is doubled in my visual field, but that verbal description is really quite inadequate. I can be a shade more precise in telling you that, because my right eye is not as good as my left, one of these 'hands', and I put the word in inverted commas, is more blurred than the other. If we are really scientific about it we have to say that a correct description of my field of view would have to be at the level of the state of each point of the field, because to talk in terms of one right hand is obviously utterly confusing. To make the point clear: imagine that my present field of view complete with my doubled hand were on a newspaper photograph- then it becomes obvious that any description of the state of the field which made use of any of the everyday terms that described what was seen on the screen - such as 'hands', 'people in the audience', 'windows' would not be an accurate description from the scientific point of view. But an accurate description could be given which made no mention whatsoever of everyday objects. A newspaper photograph consists of a number of tiny dots, each of which is in a different state: I could now produce a detailed list of the states of these points. This, notice would be a precise description of the state of the variation of intensities over the field, a perfect description of my visual field, blurred right-hand and all, without any reference to any such entities, whether objects or persons, or, indeed, any named properties, other than the quantifications used to mark the intensities of the field. So for any sensory field there are two ways of describing it: an 'entity-determinate' one, which is the one we use in a our conversations with each other, and a 'field-determinate' one, which would be used presumably by a neurophysiologist of the future wishing to describe accurately some particular distribution of a sensory field. I am sure this audience might notice something here: that one is at a conscious level for the subject observing, but the other is quite out of the range of the conscious mind, even though that mind may be experiencing every nuance that the field can provide. Just as one can look at a newspaper photograph without being aware of the state of every dot, nevertheless the state of every dot has contributed to your sensing of it. You will notice that there is a radical claim here, that in your brain, in the visual cortex, there is such a registration indicating a distribution of intensities, and much of it at any time is not consciously recognized at all. Even now as I look at you and you look at me there are experiences round the periphery of our vision that are outside our recognition. Again it takes some concentration to become aware of them - you have to resist turning you head, as we say, 'to see better', but I want you to sense better, get a clear registration of that blur and admit that you are not identifying anything. It is, as we philosophers say, entirely non-epistemic from the point of view of everyday identification, even though from the neurophysiologist's point o view it could perhaps be given its field-determinate description.

As an insightful American philosopher of the early part of this century, Roy Wood Sellars, said, we experience a field which is structurally isomorphic to the light-wave intensities arriving at our retinas (Sellars. 1932, 86), in that there are 'corresponding relations' in the distribution but no pictorial resemblance. As another modern philosopher of perception. Barry Maund, has said, we have a kind of contour map of intensities (Maund, 1993); there may be a temptation to think that some internal objects 'resemble' some external objects, but that picture is false - instead there is a parallelism between the internal distribution as a field and the distribution as it arrives at the eyes. In the same way one might say that there is a structural isomorphism between the grooves on an old gramophone record of Beethoven's Ninth and the variation of patterns in the sound-track down the side of a film of the same symphony.

The fact is, as Richard Gregory has recently asserted, we do not see things at all: it is rather that we are making prompt but learned categorizations from the visual field. It has often been said that the world does not come already labelled for us, that, where the English might see an array of different types of nuts in a shop window, the French do not see 'nuts' at all since the French language has no generic word for nuts - the French only see amandes, noisettes, cacahouettes, châtaignes. But the truth is more radical than that: we do not even immediately pick out separate entities, in spite of the fact that, as the psychologist James J. Gibson has shown us, the brain has special circuits, rather like what lies behind the Contrast knob on a television set, for sharpening what we call boundaries, all that is going on is that at the field-determinate level certain transition regions are being narrowed. It is easy to miss an obvious fact: what we call edges and boundaries sometimes are likely to mislead us. There is a large painting by Chuck Close in the art museum in Buffalo which shows a face seen through cellular glass - when one is close to this picture it is virtually impossible to see the face, not until one withdraws some distance from it and the individual cells blur does it gather into recognition. Thus there is no necessary relation between the state of the field as regards distinctness and the knowledge that may or may not be drawn from it. In short, discrimination at the sensory level is not to be equated with interpretation at the perceptual one. To say that it was would be to imply that the more sharp-sighted you were the more you knew. Acuity is not the same as acuteness. So what Sellars calls the 'patterned stimulus' is not patterned with given entity outlines. We can even experience the field without any epistemic gestalts projected upon it: the sensory in itself is devoid of information. ,It is no more than what H. P. Grice has called a 'natural sign' (Grice, 1957): a dark cloud on the horizon can be taken by those in the know as a sign of forthcoming rain, so certain recurrences within our sensory fields can be so taken, but just as a dark cloud is not labelled 'rain', for there is nothing certain about the interpretation; similarly, distributions in the sensory field are not labelled, for there is equally nothing certain about the interpretations we make.

I have spent this time establishing this point in order to say that we are not presented with data at all but a sensed field. Sellars used to insist that being was not the same as knowledge; one can specify that a little closer to our theme: to sense is not to know. There are people with brain damage who can see perfectly, but they are quite unable to look. Nevertheless we do sort out from those variations recurrences that appear valuable to us, we do categorize. By what means? In the lower animal world most categorizations come fairly automatically, but at higher levels gestalts occur to guide action. What produces them? The new neuroscience gives the answer (Edelman, 1992) - the pleasure/pain system, which has the power to imprint in memory whatever is in the sensed field when they are produced. That imprinting is tabbed with desire and fear, such that when that imprinting is matched in the sensed field again, appropriate action is keyed, approach or withdrawal. Thus the higher animals, equipped with sensory fields, are able to learn, refining their selections, and changing them should what is of moment to life change its form. But animal species have come to grief, or rather extinction, precisely because of the inability to change categorizations at short notice. What has evolved in the human case is the ability to adjust another's gestalts. One can appeal to memory or point out in the sensory field what the other may have sensed but not perceived in order to change his or her set for future action. Note that this locks in with what writers on narrative such as Jerome Bruner (1990, 47) and Paul Ricœur 1974, 328-29) have noted, that categorizations from the past once accepted as stable by the community, because of some discrepancy in the present are subjected to alterations for future action. Narrative is a temporal matter in which a canonical meaning is subjected to a dialectical transformation.

The Joke, as I argued last time , is, not merely an analogy, but an illustration. To remind you, let me take this simple example from the jokebook for children, the Oxfam Crack-a-Joke book:

What's the fastest thing in the world?

Milk - because it's past your eyes before you see it.

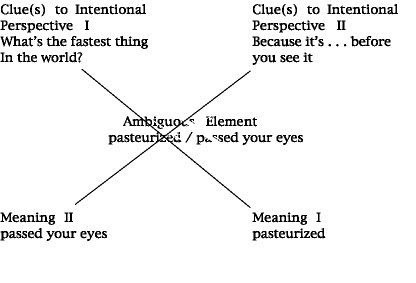

The portion of the non-epistemic over which rival gestalts will play - in this case from the auditory field - is the sound sequence 'past your eyes', which could easily be described by the acoustic physicist in terms of a sequence of frequency and volume changes, a variation of intensities, such as shown on spectrograms of speech. In itself it contains no information. Indeed, if it were recorded and the portion of the tape containing it were cut out and inserted into a tape-recording of, say, the noise of sea-waves breaking, there would be no recognition of it as words at all. But here we have two sets of clues from the past which change its meaning depending which is regarded as salient. Here is a diagram which might help to make it clear:

You will notice the similarity to Gombrich's diagram, in that there is a portion of the field over which different gestalts may range, and there are two sets of clues, from the past which induce rival readings of that portion the first clue being 'What is the fastest thing in the world?', which induces the meaning 'past your eyes', and the second clue being the frame 'It's ... before you see it.' The order in which the clues and the non-epistemic element appear may vary, for there are jokes in which we are first given the two clues and then the non-epistemic element over which the interpretations range.

All jokes without exception thus have at least five elements: the two clues, the present experience and the two interpretations for future action. I say 'at least' because there are more subtle jokes that have more clues and more interpretations. One of the Fool's jokes in King Lear has seven clues and seven different meanings that result. And, of course, it is up to the hearer to discern more still. Psychoanalysts, for example, may have heard more in that child's joke that the children heard, of milk being 'past your eyes' before you have seen it.

It is at this point we may learn from Schutz and Rommetveit. For such a transformation to take place it is essential as a method that the two agents presuppose pro tempore that they have identified the very same portion of the non-epistemic field. It is an act of faith and trust, undertaken knowing that the presupposition is only that - a presupposition. As Rommetveit puts it, 'Intersubjectivity has to be taken for granted in order to be achieved' (1974, 56). A new relevant clue is then introduced, in this case by the joker, which brings about a shift of gestalt. As with the Hamlet/Polonius example, there is no necessity that a single portion of the field be preserved, for, note, the joker here effected a canny blurring of the three words 'past your eyes' with the single past participle 'pasteurized', which not only has an additional /d/ sound at the end but is pronounced with strictly different phonemes and with different intonation and stress patterns.

Now compare a story. If the pattern is to be the same, there will be a portion of experience which in the past has been accepted according to one well-entrenched interpretation. What must emerge during the course of the story is that second clue from the past which enforces a switch of interpretations upon the present. As with the joke. the order in which the three key elements appear, that is, the two clues and the non-epistemic core, may vary. Here is a brief story, one of Aesop's fables:

There was once a blind man, who, when any living creature was put into his hands, could tell what it was by feeling it, But one time, when someone handed him a wolf-cub, he could not make up his mind. "I don't know," he said after feeling it, "whether it is the young of a wolf or a fox or some such other animal. But I do know this much, that it is no fit company for a flock of sheep." (1954)

This is a story about the story, the reason being that the story pattern can be detected twice over. In the first, the main story, the core over which interpretations are to range is the ability of the blind man himself. What has been established is his skill in identification in spite of his disability. But he is subjected to a difficult test, and the expectation on the part of the onlookers is that he is going to fail it, fail to reach the supposed expertise of the sighted. Stories are all to do with expectations founded on past assumptions. But the second clue, the words of the blind man himself, show that, as far as really relevant action in the future is concerned, he is not to be defeated although it was expected that he might. So all five of the key features are present. What is interesting about this story is that it is about recognition itself, for the blind man, although his access to the real was limited, was nevertheless able to give precise instructions on how a portion of the world was to be treated in action. By examining what was to him at first profoundly non-epistemic, since had only access to the world through his hands. Aesop has his own moral for this story: he adds 'In the same way a man's evil nature can often be recognized from his physical attributes', but interpretations are open to readers who can provide further clues to change the meaning - Can not this be read as an allegory for those who are scornful of the apparent disability of others to read the world according to the received opinion, showing that it may be someone thought to be seriously inadequate in the public view who nevertheless can correct the public language?

But the scope is wider. The pattern is that of all communication. Roman Jakobson said that the very act of speaking was the marking of the unusual from the usual. The claim here is that the word, the trope, and the statement themselves, the building-blocks of all communication, are of this form. Something is to be taken as given in order that by the addition of a correction a new interpretation can be shifted about upon the real. This was the case I argued in my last paper for IPSA.

Let me conclude with a joke told by Gerald Edelman, who used it to emphasize the semantic creativity of language. Since interpretations can shift, as they did with Aesop's story, we can do the same with this. Two American Jews, Saul and Reuben, are visiting Israel and they are keen to savour the uniqueness of that novel and interesting country. They therefore decide to go to a night-club to appreciate the entertainment that is on offer. The most successful turn of the night turned out to be an Israeli comedian. As he told his jokes, all in Hebrew, the audience were in fits of laughter, with tears running down their faces. Paul suddenly realised something astonishing: Reuben was similarly overcome, almost on the floor with laughter. "Hey, Reuben." he said. "how come you are laughing at the jokes? I didn't know you knew any Hebrew!" - "I don't," said Reuben. "It's just that I trust these people." Here is a joke that makes fun of that taken-for-granted faith that is the initial move in the story or the statement or the joke. For Reuben, the non-epistemic remained perfectly that, absolutely unintelligible. Foolishly, he trusted beyond the level of trust, forgetting that, in order to partake in the language game, we must be ready to check any assertion on the sensory field ourselves, for one day the need to correct the public language correction may be our duty. To put it in Lacan's terms, The Real is not to be ignored either by the Symbolic or by the Imaginary, and it lies outside both, outside the presupposed common agreement and the habitual private understanding.